Introduction/Conceptual Explanation

A deload is a purposeful decrease in training stress that allows the body to recover from accumulated physiological and psychological fatigue, reducing the risk of overtraining and supporting future performance.

Historically, deloads have been part of an athlete’s yearly plan to manage fatigue pre-competition (e.g., in the form of a taper) and post-competition to recuperate and set up the next training phase, depending on the scenario. Although many of these concepts originate from Olympic athlete practices, this is applicable for anyone following a training program.

Regardless of what you call it, you’ve implemented a deload at some point in your training career. This could be the occasional “light session,” this could be the additional rest days taken due to a perceived lack of recovery, or the easy week during the holidays. Effectively, they’re very similar (some are just autoregulated where other scenarios may be planned in advance).

If you’re training progressively, a deload is inevitably needed at some point. The guy at the gym who says he never needs one probably isn’t incorporating any form of progressive overload (and days with sub par performance simply go unnoticed), or could be doing more. Effective training generates a stimulus large enough to warrant an adaptation from the body. This stimulus will also generate some degree of fatigue, as explained below:

Fitness-Fatigue Model

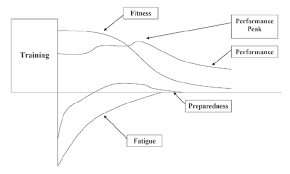

We get “fitter” as we train, but we also accumulate more fatigue. On any given day, Fitness – Fatigue = Performance. Note: this is not a perfect 1:1 rule, but we all know it works this way conceptually.

Common Strategies

The primary goal is to drop as much fatigue as possible while maintaining as much fitness as possible throughout. In most scenarios, this is a more advantageous approach compared to taking prolonged rest as it minimizes the detraining phenomenon many of us experience when getting back in the gym.

In practice, a deload involves a reduction in volume, intensity, or frequency.

This might look like…

- Reducing weight on the bar.

- Reducing volume while maintaining the rest of your plan.

- Reducing each set’s proximity to failure while maintaining the rest of your plan.

- Reducing frequency (training less) while maintaining the rest of your plan.

…or some combination of the above.

This can look very different, yet still accomplish the same goal. The approach taken should be specific to the person’s needs. In simplest terms, if your training career is a climb to the top of Mt Everest, this is where you set up camp to rest and resume the climb under better conditions.

Unfortunately, the hungry athlete often struggles to take these when they’re truly needed due to the psychological impacts of letting off the gas.

Even though it’s necessary, this often feels like lost time to many of us, but it doesn’t have to be.

Using a Taper as a Form of Deloading

During the final weeks leading up to a competition, strength athletes will “taper” their training volume as a strategy to peak for meet day.

Similar to a deload, the model we just discussed illustrates how this happens. While Fitness – Fatigue = Performance, a reduction in fatigue can result in improved performance provided training remains high enough. The primary difference here is that training loads are often increased deliberately while volume is coming down. One might suspect this strategy would increase fatigue, but that doesn’t seem to be the case and the leap in performance capability can be significant in many cases.

Provided your joints and connective tissue are in a healthy spot, you can leverage this same effect to simultaneously recover from a previous block of training and still gain a small amount of strength through the process.

One very effective way to create a taper effect is to significantly decrease your training frequency while maintaining intensity (both load and proximity to failure).

For example, let’s say you normally train six days per week:

- MON - LEGS

- TUE - PUSH

- WED - PULL

- THU - LEGS

- FRI - PUSH

- SAT - PULL

- SUN- off

You would reduce your number of weekly sessions to something like this:

- MON - LEGS

- TUE - off

- WED - PUSH

- THU - off

- FRI - PULL

- SAT - off

- SUN - off

…while keeping everything else in your plan the same.

Effectively, this results in a substantial reduction in weekly training volume due to the additional rest days, and while those three sessions are normal sessions, it’s certainly enough to ensure adaptations aren’t lost. With the additional rest (this can be front loaded or back loaded), performance will likely be slightly better on many key lifts, thus giving your body the exposure needed to facilitate neurological adaptations. Depending on your experience (e.g., maintenance requirements, etc.), you may even be able to make a small reduction in set volume and create an even greater effect–each lift would be trained in a state that’s less fatigued than usual (e.g., training ‘exercise 3’ after 2–3 working sets as opposed to 4–6 sets), creating an opportunity for more load to be used. Sometimes, simply experiencing the movement with more load than usual for a set or two is enough to break through a plateau.

You may be able to accomplish this without reducing frequency, but you would need to be more aggressive with the volume reduction. While there’s potential risk of developing connective tissue issues (in a scenario where load is coming up), reduced frequency is the first approach I recommend. I’ve found going into a session following additional rest can work wonders and have a much more substantial impact anyway. Like everything else, trial different approaches and find the strategy that works best for you.

The main idea with this is to still train hard. There are good ways to remain productive through periods of reduced training, and it doesn’t have to result in lost time.

Upon returning to normal training, you should be in a much better position to make a big run of progression.

%201.png)